MADRES CENTER RESEARCH PROJECTS 2020-2025

The MADRES Center for Environmental Health Disparities currently supports three research projects:

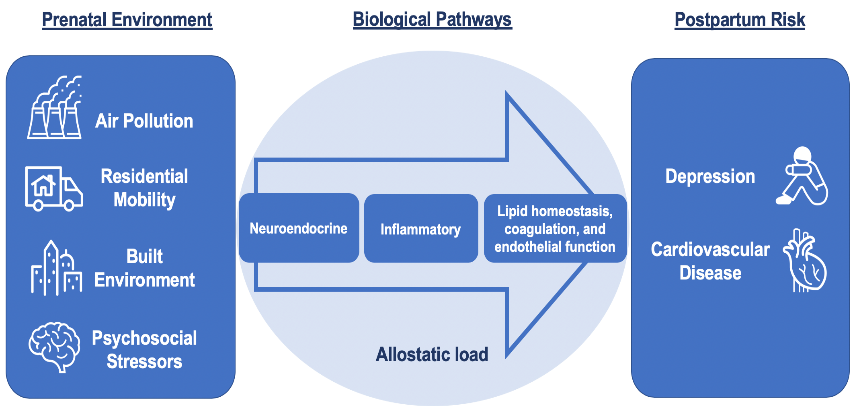

- Project 1: Maternal Prenatal Exposure to Environmental and Psychosocial Stressors and Long-term Risk of Depression is investigating the effect of environmental and social stressors on the risk of maternal depression up to four years after giving birth.

- Project 2: Maternal Exposure to Environmental and Psychosocial Stressors and Cardiovascular Risks after Pregnancy is investigating the effect of environmental and social stressors on development of cardiovascular disease risk factors up to four years after giving birth.

- Project 3: Maternal Exposure to Environmental Hazards and Social Stressors and Postpartum Allostatic Load is investigating the combined effects of environmental exposures and social stressors on allostatic load, or the wear and tear of repeatedly being exposed to stress.

To learn more about these MADRES Center research projects, read their abstracts below. To learn more about additional studies utilizing the MADRES cohort, please see Affiliated Research.

Conceptual Framework of MADRES Research Projects 2020-2025

ABSTRACT: Depression is the leading cause of mental health-related morbidity worldwide, affecting approximately 300 million people annually. Depression is nearly twice as prevalent among women than men and multiple individual and psychosocial risk factors are associated with risk of depression. Hispanic women in the US have unique risk factors for depression and other mental health disorders relative to non-Hispanic women including overcoming stress associated with acculturation as well as lower awareness and utilization of mental health care services. Traffic-related and ambient air pollutants are potentially modifiable environmental exposures that are known to disproportionately impact health disparity populations and have increasingly been implicated in risk of depression. Pregnancy is a period of dynamic biological and hormonal fluctuations designed to support fetal development that may increase susceptibility to environmental insults and effects on later depression. Despite growing evidence of the impact of prenatal air pollution on depressive symptoms in the first few months postpartum, there have been no studies on whether exposures during this critical period may increase long-term risk of maternal depression. Understanding biological mechanisms that mediate downstream effects of environmental exposures may lead to improved treatment approaches and reductions in morbidity associated with depression. As primary regulators of gene expression, epigenetic mechanisms, such as microRNA (miRNA), may be important mediators of air pollution effects on depression. MiRNA regulate numerous cellular processes, including neuroendocrine and inflammatory pathways important in depression pathophysiology. We will investigate these mechanisms and the following specific aims in 500 women in the first four postpartum years in the MADRES pregnancy cohort—an ongoing cohort of predominantly Hispanic, socioeconomically-disadvantaged women in urban Los Angeles. We will (1) investigate the association of prenatal exposures to traffic-related and regional air pollution with symptoms of maternal depression in the first four years postpartum and examine whether these associations vary by prenatal psychosocial stressors and acculturation factors; (2) evaluate whether there is a sustained response at 2 and 4 years postpartum between prenatal air pollution exposures and neuroendocrine (cortisol, norepinephrine and epinephrine) and pro-inflammatory markers (IL-6 and CRP) known to be associated with depression; and (3) determine the role of neuroendocrine and inflammatory-related miRNA in prenatal air pollution-related associations in maternal depression in the first four years postpartum and test whether they mediate associations between prenatal air pollution and maternal depression as well as examine the functional relevance of these miRNA. Results from this study may improve policy and treatment approaches to reduce the burden of depression among health disparity populations.

Contact PI: Tracy Bastain

Supported by NIH: P50MD015705

ABSTRACT: The prevalence of cardiovascular disease (CVD) has continued to climb among US women, despite greater prevention efforts. Pregnancy may provide an understudied window into a woman’s long-term cardiovascular health. Normal physiological adaptations to support a fetus can act as a stressor on a woman’s body, potentially uncovering or exacerbating underlying chronic conditions. Cardiovascular-related complications, such as preeclampsia and hypertension, may have persistent effects into the postpartum period and have been related to elevated CVD risk in later life. Moreover, environmental exposures such as air pollution have been associated with altered maternal blood pressure and lipid homeostasis, while psychosocial stressors may independently influence maternal health by increasing inflammation and risk of prenatal hypertensive disorders. Efforts to understand the roles of both the environment and psychosocial stress in prenatal cardiovascular complications and long-term maternal health risks may be most critical among health disparity populations living in urban communities, who disproportionately experience the combined impacts of multiple social, physical, and environmental stressors that may exacerbate health risks. Despite growing evidence of the impact of such exposures on maternal cardiovascular health during pregnancy, there is little to no research available on whether environmental exposures and social stressors during the prenatal period may enhance a mother’s cardiovascular risk in the postpartum period and into later life, particularly in minority populations. Even less is known about the mechanisms underlying these effects in the postpartum context, but recent studies support a key role for miRNAs in both pregnancy and in risk of CVD and suggest that these epigenetic regulators can be modulated by environmental exposures. We propose to investigate whether prenatal traffic-related and ambient air pollution exposures increase maternal postpartum cardiovascular effects in 500 women in the MADRES cohort, a prospective pregnancy cohort of predominantly Hispanic, socioeconomically-disadvantaged women. We will accomplish this by the following specific aims: (1) investigate the impact of air pollutants and social stressors during pregnancy on trajectories of cardiovascular risk factors in the first four years postpartum and examine whether these effects vary by pregnancy-related complications and acculturation factors; and (2) determine the role of cardiovascular-related miRNA in prenatal air pollution-related associations in cardiovascular health trajectories in the first four years postpartum, and test whether they mediate these associations and examine their functional relevance. These results may shed light on the contribution of environmental and social stressors to CVD risk factors in the postpartum period and could be critical for identifying women at greater risk of developing chronic disease in later life.

Contact PI: Shohreh Farzan

Supported by NIH: P50MD015705

Social inequalities related to race, ethnicity and socioeconomic (SES) status lead to spatial patterning in neighborhood risk factors, where certain groups such as Hispanics are disproportionately exposed to environmental hazards (e.g., air pollution, toxic releases) and place-based social stressors such as crime, poverty and deprivation. This “double jeopardy” contributes to their increased susceptibility and to persistent maternal health disparities, with Hispanics at a significant disadvantage compared to whites in terms of pregnancy-related maternal morbidity and mortality and access to postpartum health care. Pregnancy and early postpartum years are also a time of high residential mobility (i.e., address moves), which is important to capture to better inform exposure assessment of not only the residence but also the full geographic and temporal context around it, including the built, physical and chemical environment which may also contribute to health disparities. One health indicator thought to contribute to increased susceptibility within disparity populations is allostatic load (AL), where allostasis refers to the body’s multisystemic ability to regulate internal physiology in response to actual and anticipated objective or perceived stressors. The AL model posits that repeated, chronic exposure to hazards and stressors can dysregulate the body’s adaptive systems leading to “wear and tear” on organ systems and negative outcomes over the life course, such as cardiovascular, cognitive and stress-related diseases, with important racial and ethnic differences. Air pollution, social stressors and neighborhood socioeconomic deprivation have all been associated with AL. Yet very few studies have investigated the contribution of joint exposure to environmental hazards and social stressors during pregnancy and postpartum on AL, particularly in racial and ethnic minorities and low SES groups. Our project interrogates this question in our recently established MADRES pregnancy cohort of predominantly low income, Hispanic women in Los Angeles, CA. We aim to first understand distinct patterns in neighborhood and residential environmental exposures and social stressors in relation to residential mobility during pregnancy and postpartum, and then investigate their effects on maternal AL as an early indicator of stress maladaptation in the first four years postpartum. In addition, we will investigate whether individual-level characteristics such as demographics, psychosocial stressors and acculturation modify these effects using a multilevel framework. Our proposed project will contribute to advancing the science of environmental health disparities by providing a scientific basis for how the environment interacts with social stressors across multiple levels to impact physiological mechanisms that may signal early stress maladaptation and increased risk before onset of disease in disparity populations.

Contact PI: Rima Habre

Supported by NIH: P50MD015705